Jayson Gentry knows the daytime sky isn’t always blue.

Jayson is passionate about alternative energy sources and works as a wind site assistant manager in Medicine Bow, Wyoming. Sourcing his night light from a coal-fired stove in his cabin while drinking ranch water, he surfs and reads intently about the need to set aside some of his salary for an unanticipated emergency. This is Jayson’s first job, and it pays him very well. Timing is everything. In the midst of the pandemic, he was living at home and completing his education at the University of New Mexico. But the family business was a group of restaurants in Albuquerque that didn’t fare well. No business revenue, employee layoffs, and a budget at home that became very tight. His experience scarred Jayson.

Coming out of the pandemic, Jayson moved 600 miles north for a green energy job to a town in the county of Carbon, not far from Laramie. Weekend bow-hunting, fishing in Rock Creek, and an outdoor lifestyle are Jayson’s new avocations. But, he is thinking about how to manage his money, and with a good job, he is determined to set money aside. He begins poking around the web.

“As you prepare to invest, it's important to set aside some money—about the equivalent of 3 to 6 months' of living expenses—in an emergency fund.”1

Sound familiar? These words written on the site of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) are often rephrased as,

“Experts say you should have 3 to 6 months of living expenses just in case.”

As if this is the chorus of financial planning song #8 sung with vigor at conferences, the hallways of wealth advisory firms, and among certain CFPs.2 But why? The working poor wouldn’t want to sing along. What if a household is committed to a rainy-day fund but is maxing out credit cards for basic consumption needs? When basic food, shelter, and clothing expenses are pinching a budget, it is inconceivable that setting any money aside makes sense. On the other end of the scale are the wealthy, who are probably tone-deaf because they have the emergency fund risk handled.

More generally, where does the length of time rule of thumb come from? Why is it 3 to 6 months? Why not 12 months, 18 months, or 24 months? Trade-offs exist everywhere, not the least of which is a rainy-day fund that kicks in only if an emergency need arises with some probability against the certainty of a higher living standard. Periodic contributions to any set-aside fund are, by definition, unused for current spending. Rainy-day funds, their establishment, and their magnitude need careful guidance and a fine-tuned approach. Sure, Jayson feels the need to set up a rainy-day fund, and an objective approach using Personal Finance Economics should enjoin his decision. If trade-offs are considered appropriately, Jayson has knowledge on his side.

Who has an Emergency Fund?

We know funds held for emergencies, or what data gatherers who constructed the National Financial Capability Study call “rainy-day funds,” are more likely to be held by households with higher incomes. Below is a roll-up of the data. When asked, “Have you set aside emergency or rainy-day funds that would cover your expenses for 3 months, in case of sickness, job loss, economic downturn, or other emergencies..,” 24,429 of 27,091 respondents gave a “Yes” or “No” (rather than “Don’t know” or “Prefer not to say”). Taken together, the overall proportion who said Yes was just above 52%. The chart below shows a rising stair-step of the proportion of households who hold rainy-day funds as incomes increase.

Personal Finance Economics frames the rainy-day question as a decision to be made. It starts with the assertion that any funds put aside for an emergency are funds unavailable for consumption. In other words, emergency fund contributions are monies taken off the table that could otherwise be spent. Money set aside to fund 6-months of living expenses isn’t without cost. As a limiting case, a household could set all of its income aside for 6 months, but then, of course, it couldn’t pay for the basics of life. As a household allocates more for current consumption to handle the basics, it takes away from savings. But how far to go? If you adopt the mythical 6-months of living expenses rule, you will have less fun when you contribute to your emergency fund account and thereafter. How big will an emergency fund impact the periodic living standard? That is the key question to be answered.

Jayson’s Case Study

Let’s rotate this back to Jayson to measure how his preference for a reserve fund will impact his daily financial life. Jayson is 25 years old, has yet to marry, and has no children. Jayson has monthly payments of about $1,500 that cover his new 30-year mortgage and property taxes on his home. Jayson’s goal is to have flexible savings (non-retirement funds) available that could replace 1-year of after-tax income.3 Jayson earns $75,000, expects 1% annual real earnings growth, receives 5% 401(k) contributions by his employer, and currently has $6,000 in a checking account and $8,000 in a brokerage account. He plans to set aside his brokerage account cash and add $7,000 nominally per year for the next six years to reach his target of roughly $50,000, unadjusted for purchasing power. We assume any financial assets allocated to a reserve fund earn a return that keep pace with inflation, e.g., a 0% real return.4

Jayson’s optimal annual living standard under both the reserve and no reserve alternative is traced out in the chart below from his current age to his assumed maximum age. Jayson’s optimal living standard will decline by about 19% each year for the next 6 years then is loosely comparable annually for the balance of his life. The highest obtainable living standard occurs around age 55 for the balance of Jayson’s life and is partly due to the payoff of his new 30-year mortgage. The general rise in living standard is the highest obtainable for Jayson because some of his future assets are not easily “borrowed against” from the time he is 30 to age 55. Social security retirement benefits and 401(k) values have built-in access constraints generally unavailable during mid-life until age 62 and 59 1/2, respectively.

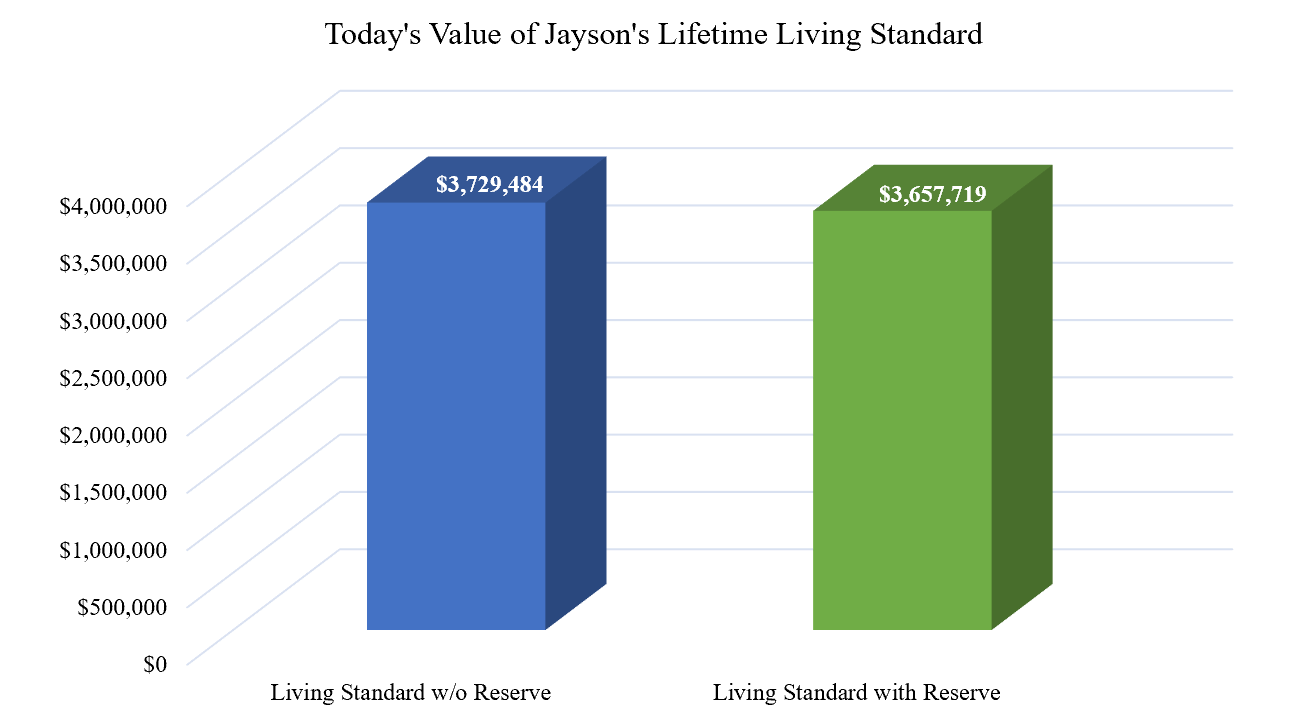

The values in the chart above can be added up to create today’s value of Jayson’s optimal lifetime living standard. This is the metric Jayson can use for decision-making. Sums are in the column chart below. In today’s dollars, Jayson has $71,765 higher lifetime living standard if he does not fund the reserve fund as intended. The right-hand side of the chart shows the lower lifetime amount if a reserve fund is established. Jayson would contrast his choice of a slightly lower living standard with the feeling he had that after a few years, he would have a fund that could cover about a year of after-tax income. He is now equipped to evaluate the trade-off.

The Choice

The light bulb is on, powered by economic technology. What should Jayson do? As noted in footnote #3, a more systematic analysis of the 3-month, 6-month, 9-month, and 12-month time periods could be created to give Jayson a small number of living standard outcomes for different reserve fund quantities and contribution amounts. His choice can now be driven by his preferences in light of the projected economic outcomes. Jayson is endowed with the knowledge to be a more informed decision-maker. Jayson became more risk-averse after his family's financial crisis, so the odds are high on him moving toward some targeted reserve fund level.

An additional important takeaway: whichever pathway Jayson follows, he has a spending target for his economic happiness because modeling was undertaken for both alternatives under economic principles. Coming into the decision, Jayson always had an actual way he was spending his money. Either the reserve or w/o reserve option will offer Jayson a solution, and either of these choices will be accompanied by a recommendation about how he should change his actual spending.5 Jayson may find that while he has a mortgage with its associated costs, his other monthly expenditures are so low that he can establish a reserve plus increase his discretionary spending over his actual state. The alternative is plausible, too. Jayson could be spending far too much relative to his optimal level of spending, and with a decision to set money aside for a reserve fund, spending would have to be lowered dramatically. That could lead to a lights-out moment for Jayson and a few challenging months to re-orient life to a sustainable living standard.

Here is a sample from a quick search: Modern Frugality, Vanguard, and NerdWallet.

The one-year target is a single scenario to be compared to the no-reserve benchmark case. Once the model is built, one can quickly look at other reserve amounts and timing contributions to arrive at a menu of reserve fund/living standard alternatives from which an individual or household could make their preferred choice.

Jayson’s complete economics-based financial plan, inputs, and assumptions may be downloaded here from my website.

The financial planning process that compares actual to optimal for Jayson would be an approach similar to the Diaz household.