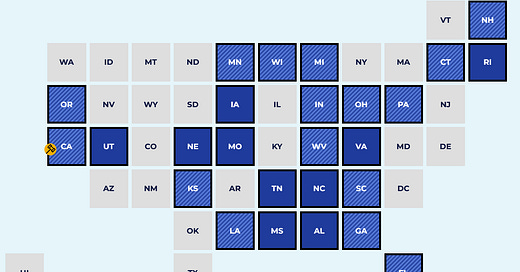

How do you feel about states requiring educational investments in personal finance? California made news this summer with its personal finance graduation requirement. Next Gen Personal Finance has tabulated the current state of mandates for a personal finance course in secondary schools. Below is the graphic from their interactive dashboard. In recent years, Stanford has hosted conferences for personal finance teachers, and another one is coming up. Given that half the states are on this educational bandwagon, more programs are to come.

Who determines the training content? Stanford aside, most major universities are populated with faculty who have little interest in personal finance research and education. Universities may offer a course that checks a box. We need more faculty who can take the economics and financial research of the last twenty years to build relevant content for personal finance decision-making. That is one of the reasons I decided to write PFE on Substack. Aaron Stevens and I have a new economics-based personal finance textbook, yet we have no competitors; embracing the current state of economic knowledge to make good personal finance decisions shouldn’t be a barrier to serious content providers.

What were you doing at 17?

Most think that knowing something about money is an essential life skill, and academics have found correlations between financial literacy and financial behaviors. Among those with more financial education, there is less bad financial behavior, e.g., less likely to take out a payday loan or have debt go to a collection agency. However, numerous personal traits might cause better financial behaviors.

Will a 17-year-old who earns an A in personal finance have a better economic outcome later in life because they took a high school course? The question doesn’t pass a reasonableness test. What were you doing at 17? The serious side of the mandate question is that taxpayer dollars are allocated to these programs.

Venture into this prior post, and you will learn the decay rate of financial education. No worries; you can offload your questions to me!

New subscribers and followers, the story below includes a link to test your financial literacy. Have fun with it.

How do you feel about your financial knowledge? Need more? Want more? Christy Lee might. This year, Christy's journey moved from being a full-time Big Four consultant to a food writer. Christy has built wealth, captured a few year-end bonuses, and used inspiration from Ruth Reichl’s written word and Laura Wilson’s photography to develop a subscription-driven foodie paradise—writing and photographs for the urban sophisticate; none of the Pioneer Woman’s flowery, advertising-driven cuteness. Hunkered down in a three-bedroom Craftsman off Orange Grove in Pasadena, Christy has found her lair. No more escapes to LAX on Monday morning with a Thursday evening return. She even has time for a round a week at Brookside Golf Course near the Rose Bowl.

Christy is ready to receive advice, not give it. She is the financial type. Generally confident about financial matters, given her training and UCLA education, she is wise enough to know that her experience advising Fortune 500 firms about their cyber risk problems may not translate to good financial decision-making. That can be outsourced, too, when time needs to be spent stylizing the next best Paella.

A couple of times a month, Christy thinks about her finances. Bills are to be paid, and reading is to be done. Like my students, Christy knows that a household’s transactional banking and investment needs can be efficiently run using an investment company’s brokerage account with a cash management feature. Bill-pay, reimbursed ATM charges, normal check-writing, a mobile app, and research tools are plentiful from good providers. Fidelity and Schwab are two of them.

Christy’s occasional need for financial guidance is a good example of what we see in the economics literature about financial education decay. You may educate yourself, but financial education, like any education, needs to be revisited. Recently, a former student contacted me about good spots today for high-interest savings accounts. “Jacob” had gone through a semester course in life-cycle economics: learning the language, model building, financial planning, and testing; a decent student. Even with the know-how, there can be knowledge gaps when personal finance is not your life. When one thinks of it, there are a lot of knowledge gaps among financial advisors and personal finance writers.

I asked Jacob: “ what are your intentions for saving money? “I want to save for a home and have an emergency fund, he replied.” Made sense to me. Once he expresses that preference, he can take anticipated savings away from his present-day living standard and allocate them to his two objectives. My opinion was to avoid standard bank savings accounts because inflation-adjusted returns are negative, and I-bonds should be explored to remove any inflation risk. With the acceptance of more return risk, I suggested that a Roth IRA with funds invested in a total market index fund could be another good choice.

Financial Education Recedes

The details of these recommendations are unimportant to this piece. But, even a college-educated person who learned specific personal finance information had questions. Christy Lee has both sides of her brain working, and she has questions. Learning moments can deteriorate. Kaiser, Lusardi, Menkhoff, and Urban (2022) found in a large statistical analysis of 68 papers that while financial education positively affects financial knowledge, such education is less impactful on financial behaviors.1 After 20 months or so, the value of the financial education wanes. This result may speak to an interesting conundrum we see among the population. Individuals are much more confident about their financial knowledge than objective measures of such knowledge, like a financial literacy test. People are generally optimistic about their abilities, but when put to “the test,” they don’t do so well.

Answers to an at-the-moment test for which there has been no preparation are likely to be less than completely correct. Here are the results of the six (6) objective financial literacy questions set across 23,617 respondents to the 2018 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS). While there is a slight upward trend with age, an overall mean score of 2.96 correct answers out of 6 isn’t a passing grade, and the results have been generally this way since the NFCS began collecting data in 2009.

In the face of these results, confidence remains. In the chart below, respondents were asked to rank their financial knowledge on a 1 to 7 scale. I truncated the age at 80 in the chart for readability. Readers might be amazed that about 75% ranked themselves as a 5, 6, or 7. Yes, the same sample that produced the financial literacy performance. Why?

Financial Literacy and Feelings about Financial Knowledge

One obvious piece of the puzzle is that financial literacy may not matter. That statement has enormous implications. The primary objective of the public policy push for financial literacy education is that households will make better decisions and engage in better financial behaviors. What if objective financial literacy was less related to financial behaviors assumed to be preferred and causally related to better economic outcomes? Results matter most.

Nibbling on the edge of this topic, in recently published research, we did not find a cause-and-effect relationship between higher levels of objective financial literacy and higher perceived economic outcomes.2 In this paper, we created a reflective economic perception index which rolled up into a single measure for a respondent’s answers to three questions:

1. “Overall, thinking of your assets, debts and savings, how satisfied are you with your current personal financial condition?”

2. “In a typical month, how difficult is it for you to cover your expenses and pay all your bills?”

3. “How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement? - I have too much debt right now.”

More financial literacy, as measured by the number of correct answers to test questions, did not result in a higher perceived economic outcome. Moreover, it is easy to imagine that if a household believes their economy is okay, their self-assessment of financial knowledge would align. At the very least, they wouldn’t be pessimistic about their plight. We think how one feels about their financial condition is important. Answers to such questions are personal judgments linked to satisfaction rather than a financial behavior a researcher may deem as bad or an objective economic output measure such as wealth, income, or consumption. A key “inside baseball” point: when researchers correlate a score on a financial literacy test to certain financial behaviors like credit card usage, they evaluate data at a precise moment in time that likely doesn’t capture the whole story. Many households often use their credit cards and are perfectly happy with their financial condition.

How can these thoughts be reconciled with Christy and Jacob? Obtaining answers to financial questions when needed may be the best medicine. There is no decay, and quality content will be up-to-date.

Kaiser, T., Lusardi, A., Menkhoff, L., & Urban, C. (2022). Financial education affects financial knowledge and downstream behaviors. Journal of Financial Economics, 145(2), 255-272.

Puelz, D., & Puelz, R. (2022). Financial Literacy and Perceived Economic Outcomes. Statistics and Public Policy, 9(1), 122-135.

As a college student, it's great that states like California are pushing for personal finance education in high schools, but it's unfortunate that many schools still don’t prioritize these essential skills. Learning about managing money early on can set better habits, but at 20, most of us aren’t focused on long-term financial goals. Plus, financial education tends to fade over time without regular application.

Not directly related to financial education, but potentially of interest to your readers:

https://econpapers.repec.org/article/inmormnsc/v_3a63_3ay_3a2017_3ai_3a1_3ap_3a213-230.htm