Two weeks ago,

continued her home economics series on The Purse, which featured the financial history of a Coloradan who, after a mid-life divorce, had a financial story to share. “Colorado” wrote:I LOVE your Home Economics series! It’s so interesting to see what other people’s financial lives look like. In the comments on your last post, you said, “People with good finances are always more likely to share than those with more complicated money situations.” Ha! That inspired me to send you my story, since my finances are a hot mess, and maybe that will resonate with some of your readers!

If you read any of the four home economics pieces, they are candid and detailed. The stories are gifts, offered with feelings, relatable, and with a high level of personal finance information. They capture much of the same information my students collect when producing a financial plan for their actual clients in my life-cycle economics class. Colorado’s solution, the paradigm, not the numbers, is your paradigm, my paradigm, and the future of financial planning. I’ll never know Colorado, and I hope she finds this piece. Subscribers: this is a short read; numbers only as necessary, and comments are open to all.

Quick Background

Colorado is typical of Lindsey’s readership: women who trust Lindsey and value Lindsey’s work. Lindsey’s Home Series captured my subscription, and to be clear, I am a guy and can make zero contribution to the topic of motherhood, another focus of The Purse. In my profession, we’d call the Home Series a sequence of case studies. I wonder if financial advisors and CFPs understand how valuable these stories could be to their practices. Prospects for financial planning services have no idea where to start or what the outcome of the effort will be. Pointing them to these stories or Personal Finance Economics would help.

Colorado took a risk and would benefit from a plan, and I hope my readers find these three lessons valuable.

The need for financial planning guidance is vast, not limited to wealthy or high-income households. Colorado represents the many in the middle of the income distribution. Subscribers at any level can benefit.

Information about financial accounts, income, and future prospects is required to approximate the plan producing the highest living standard. Past spending behavior is long gone. Colorado’s state of affairs relies on her current resources but heavily on future details. Doesn’t it make sense that while Colorado is working today, her future Social Security retirement benefits should play a role in today’s planning? Kind of like future inflation, investment returns, and taxes? The end game matters. Colorado’s longevity and work life are musts for discussion, and whether at Colorado’s max-age, what happens to any estate that might exist.

The optimal planning result will prescribe the highest living standard and any savings behavior this year and every future year to achieve these results. Of course, the plan should be revisited annually or when conditions change over the balance of the assumed lifetime. Colorado’s highest living standard is shown below. In economics-based planning, the ceiling number leaves room for Colorado to determine the type of spending to reach the ceiling. How Colorado spends her money is her choice. If expense cuts are needed, Colorado determines what to cut to reach the target.

Colorado’s Finances

The current state of affairs,

Colorado is self-employed, calls herself a freelancer, and tries to generate $4,500 per month. Given that she is 63, she can take a lower Social Security retirement benefit today, wait until age 67 to receive the full retirement benefit, or defer to age 70 and take an enhanced Social Security retirement benefit.

Colorado has $7,000 in bank checking and savings and about $44,000 in retirement plans.

Colorado’s home is valued at $446,300. She has a 2.75% APR mortgage with a $116,000 remaining balance. Her monthly payments are $1,092.

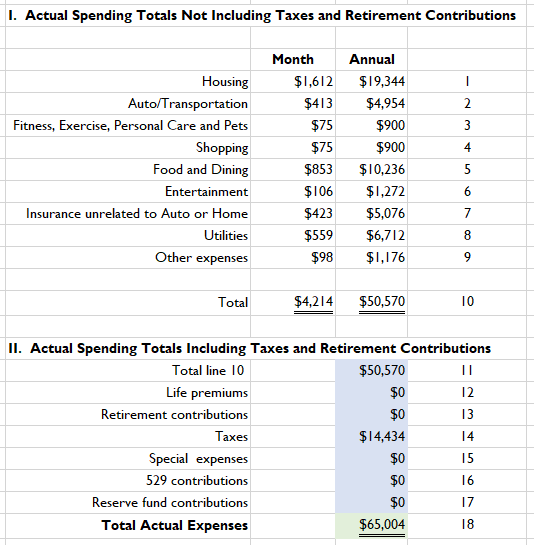

Colorado’s expenses are itemized in

’s posting. I rolled them into an expense worksheet, and the monthly and annual totals are listed in this table.1 The annual expense total before any consideration for federal, state, and social security taxes is about $50k (Panel I, line 10), and it is pushed up to $65k with taxes (Panel II, line 18). Colorado’s taxes are relatively high because her state has an income tax, and she has to pay both sides of the social security tax, 15.3%.

Colorado’s New Financial Plan

Is Colorado in a “hot mess?” Little savings and an eat-what-you-kill freelancer job puts a lot of pressure on the job to support Colorado’s living standard. A lot is happening in Colorado’s future, like ours, and it is time for a short tutorial explaining why economics-based financial planning is better than any conventional method.

Optimal planning adds time to the mix and introduces every future consequential financial element known today. Colorado’s financial plan for 2024, 2025, etc., is informed, for example, by expectations about Colorado’s Social Security retirement benefits, savings rates-of-return, inflation, and any inheritance from Mom, who is still alive. That includes entering an uncomfortable space and discussing the length of work-life and longevity. For how long does Colorado expect to work and live? It is a tough question that requires a response.

For Colorado, I don’t know her longevity expectations. It appears Colorado is expecting to work, and family history suggests a longer life (Mom is 89, lives by herself, and owns her $450k home that may be sold when extended care is needed). When generating the baseline financial plan, I assumed Colorado works until age 70, when she begins pulling her Social Security retirement benefits. Colorado’s max-age is set to age 92. No gasp is necessary because these assumptions can easily be changed. The economic effects are predictable. Fewer years of work will yield a lower lifetime living standard. More years will increase it. A higher max age lowers the annual living standard to accommodate more years of living. A shorter life and a higher living standard follow.

The Optimal Plan for 2024

Colorado’s highest sustainable living standard requires a software engine, and I use MaxiFi, a product from Economics Security Planning, a firm built by

. Colorado’s optimal plan to round out this year is below, and the entire financial plan can be found at the bottom of this page.The Explanation

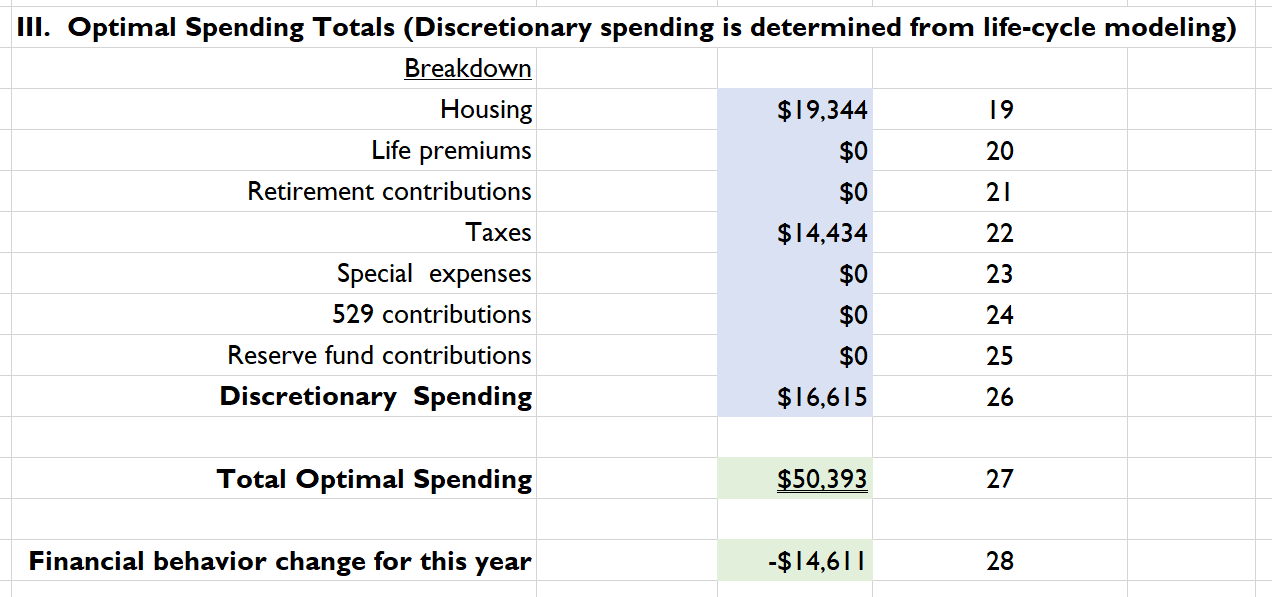

Colorado’s optimal financial plan boils down to the simplicity of Panel III. This is Colorado’s first-year guidance derived in the context of the next thirty years that will take her to age 92. Lines 19 through 25 are placeholders because they are usual considerations for most households. For Colorado, most are zeroes except a restatement of her housing expenses in line 19, and an estimate for her federal, state, and FICA tax amounts in line 22.2 Line 26 is very important. It is found in the optimization method and is the key component of Colorado’s magic number, a topic I have written about before. Listed simply as discretionary spending, the interpretation is that Colorado can spend $16,615 on all other expenses above housing and taxes. The best baseline planning requires a substantial cut in expenses, and some of the expense cuts involve funding new savings. Which expenses to cut? That is Colorado’s choice.

Why is her optimal discretionary spending so low? Because she needs to save more immediately in amounts listed in the table below. The savings prescription is the result of optimal planning and sizeable amounts are recommended for Colorado’s remaining work years, initially setup to be through age 69. At 70, Colorado has SS retirement benefits as an income substitute, but they provide less than 60% of her former after-tax labor income according to my estimates. Built-up bank checking and savings begins funding the living standard at age 70, as seen in the table.

An Alternative

Are austerity measures unavoidable? Of course not. There are always trade-offs. Here is one.

I played what-if on work-life balance, keeping Colorado at work for three more years until she turned 72. Any drawdown of retirement account funds could be pushed back until age 73. In my opinion, this alternative provides a significant difference for this year and gives Colorado added flexibility. In the table below, line 26 increases to $22,323, and less near-term cost-cutting is the payoff in the short run. Not evident in this one-year snapshot is that three more years of freelancing increased Colorado’s lifetime living standard by about $163,000. That is a financial shot in the arm. Only Colorado knows whether working more makes sense for her.

Summing Up

It will be interesting to learn how Colorado responds. I am counting on

to share. How would you respond? We found a 63-year-old woman with little savings or familial financial support, the ability to work, and knocking on the door of Social Security retirement benefits does have a path. We all have paths. Readers who look at the full financial plan will find that I recognized Colorado’s concern about her HVAC system and took some money off Colorado’s discretionary table to fund $2,000 in maintenance for the next ten years. I assumed very low savings returns on the resources side, just enough to match inflation expectations. I also ignored any inheritance from Mom, which is likely limited to the home she owns. The U.S. tax system stayed static, too.Thank you, Colorado, for sharing.

You can download a generic expense worksheet I offer subscribers. It is located here at the bottom of the page, affiliated with the January 2024 listing.

The table is my setup for reporting optimal results and begins generic after using MaxiFi,

, fabulous software. The tabular format applies to you, Colorado, and any household.

Really puts into perspective that it may not always be about how much you make, but how you spend/save

This was a very interesting read, and I think it speaks to the overall importance of social security tax and benefits. It is super interesting and highlights the importance of how spending/ saving can affect one's financial means.