Practicing Financial Planning: Living Standard is Indispensable

Satiation is an important ingredient

How many hotdogs can you eat? How about desserts? Often, we think about consumption related to food, and we have our limits. However, Americans appear to push those limits. 42% of the population is clinically obese, and we sure have an ample supply of diet books. Maybe we are not gorging enough on good sense. Satiation, the feeling of being satisfied, is an assumption underlying the economist’s view that the value of “more” becomes incrementally more but at a decreasing rate. It is an ingredient that helps us understand economics-based financial planning.

Consumption and food and financial planning? Let me clarify with a personal food story. I am not so much into desserts. But a juicy In-N-Out cheeseburger with lettuce and tomato? I am into those. It's almost as good as a trip to Maple & Motor. At lunch, a double-double does me just fine. If I am standing under Snyder’s yellow arrow after coming off an aggressive treadmill workout and my number is called a second time, I am at the counter if it’s the last time my heart beats. A third and a fourth cheeseburger? Not so much. That is an example of satiation or “diminishing marginal utility.” At least in cheeseburgers.

The same concept applies to consuming shelter, clothing, goods, and all that life offers. It drives the idea that practical financial planning for the individual or household should be focused on a lifetime of living standards. Today’s income and wealth are important to today’s living standard, but the future matters, too. Future income, prospects for longevity, changing household composition, and the need to consume over time. Aaron Stevens and I put it this way,

“Economists use utility as a measure for happiness, and assume that rational people will choose to maximize their utility through time: rational people will want to smooth consumption over their lifetimes at the highest sustainable level because they want to maximize their lifetime expected utility. This result is fundamental to a life-cycle view of financial planning and wealth management, and gives the practice of financial planning its intellectual underpinning.”1

Living Standard is Key

Is there any concept more immutable than living standard-driven financial planning? We change jobs, go back for more schooling, move to a different region of the country, take out a loan, save money, seek higher investment returns, and manage risk with at least an intrinsic desire for a better financial outcome for us and our family. These targets fit within the context of charitable giving, leaving a legacy, and receiving an inheritance if lucky. The intellectual foundation of the life-cycle model has room for all the practical elements of people’s lives. The model explains why people save at any given moment and why they don’t. It isn’t just a black box built by a hairy-eyebrowed economist who teaches it to grad students and hopes somebody beyond the groveling Ph.D. aspirants pays attention. It is as roomy as a house and decorated with all the attributes of our financial lives. It is pretty amazing.

A Life-Cycle Model Illustration

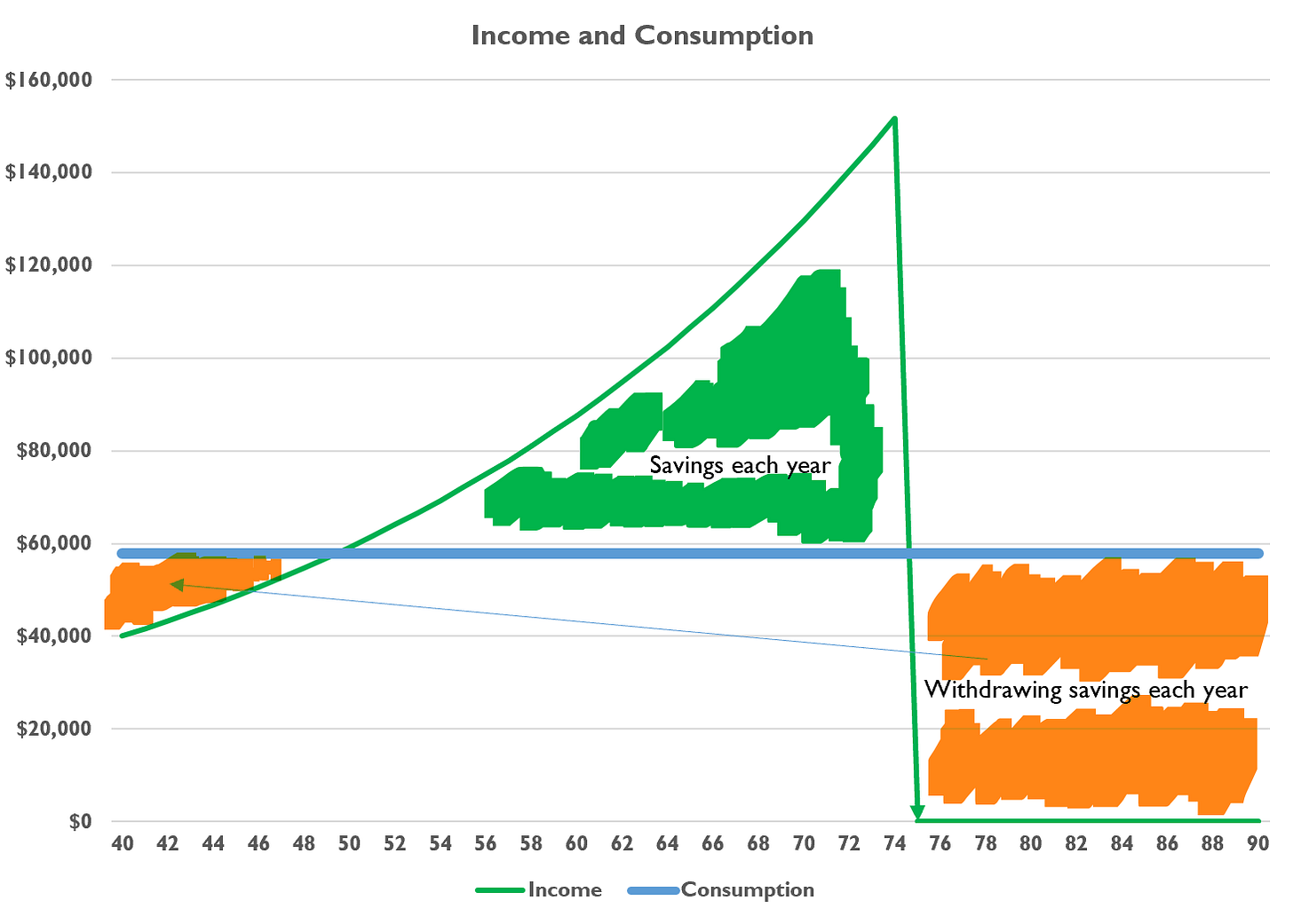

Let’s take a 40-year-old single, Patrick, who would like to work another 35 years and has the longevity to age 90 if he can lighten up on the desserts. In the graphic below, the green line traces his expected income growth from today’s value of $40,000 at a real income growth rate of 4%. At age 75, his earned income drops to $0 at his expected retirement. It is a simple example that doesn’t include taxes, returns on savings, social security benefits, etc., but illustrates the solution to consumption under these conditions. The question is, what is the optimal level of consumption that maximizes Patrick's lifetime expected utility? Software is involved in handling math, and the optimal amount of consumption in today’s dollars is just under $60,000. That is the optimal living standard path as of today.

What does that mean in terms of planning? Until age 49, Patrick can consume at rates higher than his income. That is the shaded orange area. Yes, he is borrowing money and accumulating debt each year during this early time frame. The green-shaded area shows the increasing differential between annual income and annual consumption. Debt repayment begins at 50 because income is more significant than consumption from 50 until his retirement date. From age 50 to 75, Patrick will always consume less than his income, and he will begin building a savings balance to fund his retirement years. That flips, of course, once retired when accumulated savings are systematically depleted to cover consumption for his remaining years.

Details Matter

Patrick’s example is simplified, and all the details regarding tax law, investment returns, governmental benefits, inflation, etc., determine the living standard result. Real-world attributes do not diminish the importance of the process. For sure, the numbers adjust, but the procedure is the same because the economics are sound. Mix the financial attributes. Shake in some satiation. Calculate today's optimal consumption path that creates an individual’s highest, sustainable level of expected utility. It is the core concept that all financial planning practitioners should follow to guide client decision-making.

Puelz, Robert and Aaron Stevens, Economics-Based Personal Finance, Economics-Based Personal Finance: A Core Book, Spring 2023 Edition. p. 53.