Investment Risk and JG Mullaney

Living standard risk and the decision when to retire

In a prior post, I introduced how to solve the “when to retire” decision crafted for the attributes of the hamburger-loving cardiologist JG Mullaney and his wife Beth, who live in Dallas. The Mullaneys want to retire at age 60 and travel the world but do not know the economic cost of achieving that goal. Both are 35, and they have targeted another 25 years of work in a lifetime that is expected to span until age 90. They need post-retirement resources, which will dictate a specific spending and saving pattern today to achieve their goal. But, the “when to retire” question, like any other financial decision, entails a decision made under the uncertainty about future income, changes in laws that affect household wealth, and investment performance. In this follow-up, the focus is on investment risk and return.

The economics-based approach began with the Mullaney’s question about how much to save to retire at 60 while recognizing they will reduce their nearer-term living standard to reach that goal. Then, iteratively, how much additional benefit would accrue to their current standard of living if they retired at age 62 or 65? Working longer accrues more economic benefits. However, they defer their dream of traveling the world. Working more years beyond 60 is five fewer years of fun, and the Mullaneys can assess that cost to their well-being. They are best informed only when the best representation of the trade-offs is put in front of the Mullaneys. If they have an investment advisor or wealth manager, alternatives are developed, and the Mullaneys use their utility, taste, and risk tolerance to choose.

Investments Matter to Living Standard

In this note, I intersect Personal Finance Economics with the wheelhouse of a private wealth manager and combine the optimization of the Mullaney’s living standard with the prospects for their investments. A key point is that investment risk and return are not singular in their importance to the Mullaney’s financial plan and choice of when to retire. Their living standard depends, among other items, on the work-related earnings of JG and Beth, the taxes they pay currently and prospectively, real asset values, social security benefits, and the returns they receive when saving money.

The Mullaneys may find the annual percentage yield (APY) of their local bank’s savings account offerings is less than 1% today. At the same time, an investment in the stock of a dividend-paying company is likely more significant. But, of course, the risk that the value of the stock will decrease or increase in the future will reveal an actual return different from the return expected while it is being held. An obvious point: a stock investment has more risk than a bank savings account. What is the effect of stock risk on living standard risk? Higher returns on investment produce the happy outcome of lowering the future need for more savings, and “savings of savings” translates to a higher living standard and more discretionary spending. If the Mullaney’s save from age 35 to 60 and earn 25% year-in and year-out on their savings, rather than 2%, a sunny future is in store. But it may not be that way. Stocks are volatile. If the Mullaneys invest their savings in a safer investment, what is the effect on their budget if they retire at age 60?

The Mullaney’s Investment Risk and Living Standard Risk

Investment risk creates living standard risk, but the range of future living standards needs to be cast within the development of a complete financial plan. The effect of future changes in investment performance can be measured and juxtaposed against all the household’s resources. Indexed social security retirement benefits, the value of a home, the ability to work and earn an income, the choice to switch geographic location, whether to own or rent a home, etc., matter to the Mullaney’s living standard and possess risk attributes different from financial securities. How does the Mullaney’s financial plan change when investment risk is introduced? The answer begins with determining how the Mullaney’s sustainable lifetime living standard adjusts for future changes in investment performance.

To illustrate, new financial plans for the Mullaneys are developed for the “Retire at 60” and “Retire at 65” choices where the Mullaney’s brokerage account and 401(k)s are evaluated across two broad investment types.

A “safer” investment scenario where all the Mullaney’s financial assets, including 401(k)s, are invested in a portfolio composed of 80% in the Total U.S. Bond Index and 20% in the Total U.S. Stock Index

A “riskier” investment scenario where the investment proportions are switched: 80% in the Total U.S. Stock Index and 20% in the Total U.S. Bond index

A standard technique called “Monte Carlo simulation” is used to help understand the future investment performance of these securities. The financial plans are available upon request.

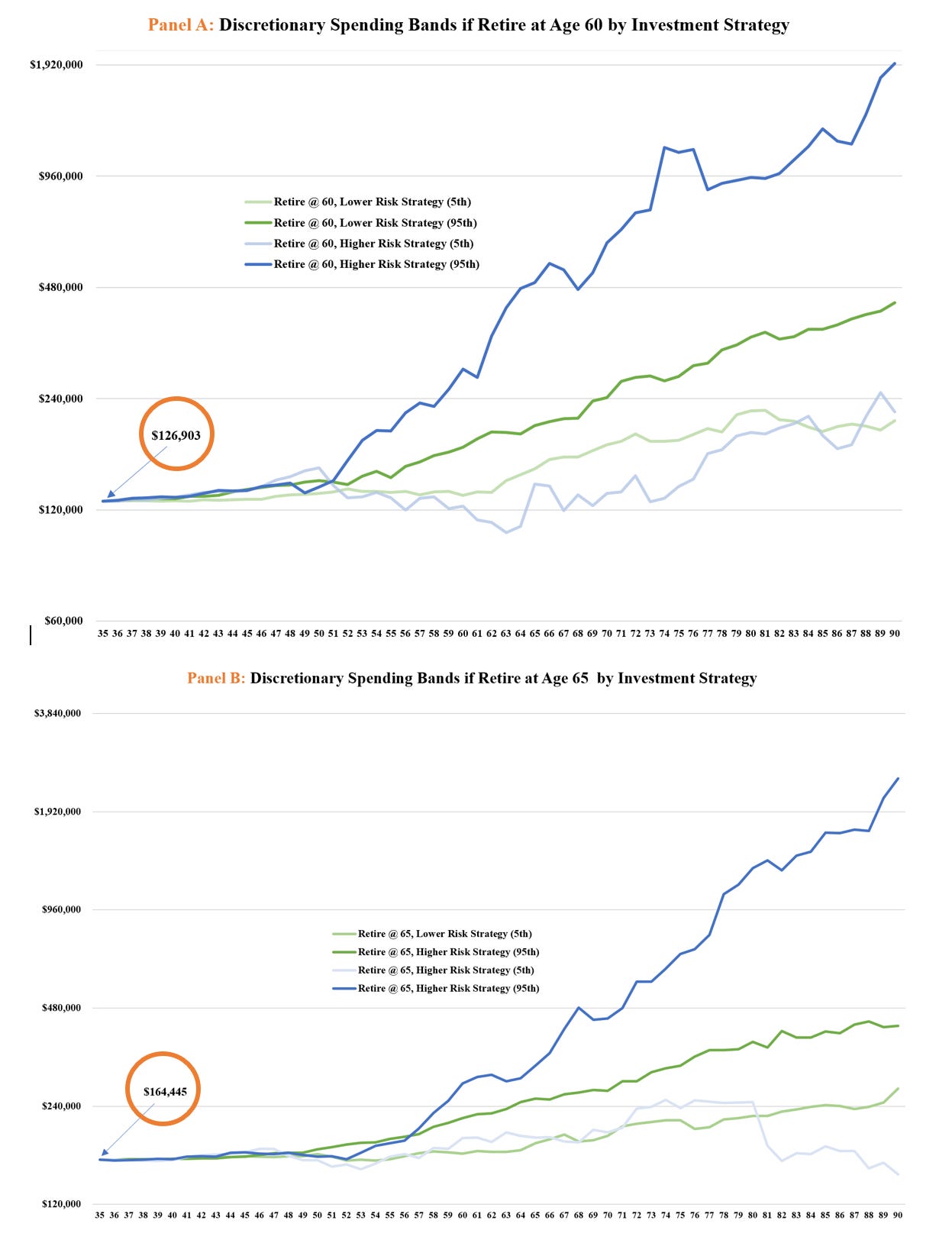

Panels A and B display discretionary spending bands for the retirement decisions of people aged 60 and 65, respectively. Regardless of the Panel, tracing the bands from age 35 to age 90 represents the range of plausible trajectories of optimal discretionary spending differ by the impact of investment risk. Blue bands show how discretionary spending varies for the higher-risk (riskier) strategy, and green bands show how discretionary spending varies for the lower-risk (safer) strategy. The lower, lighter blue line is the 5th percentile of all spending trajectories when investing in a higher-risk stock portfolio, and the dark blue line is the 95th percentile of all trajectories for that same portfolio.1 In other words, the gap in optimal spending totals from the 5th to the 95th percentile of the blue lines captures most of the potential outcomes for the Mullaney’s optimal spending path given the risk-return characteristics of the riskier portfolio. The same percentile gap interpretation is valid for the green lines, except they are derived under the safer investment strategy and, as a result, are more narrowly differentiated over time.

How the Mullaney’s Use this Information

JG and Beth have a higher current living standard if they elect to retire at 65 rather than 60. Retiring at age 65 yields optimal spending in the current year of $164k, greater than the $126k if the Mullaneys retire at age 60. An expected outcome is because of more years working, higher levels of post-retirement 401(k) benefits, and higher social security retirement benefits.

From this point, optimal spending, e.g., the optimal living standard, fluctuates based on investments. Indeed, in some ways, the trajectories of the lines on the age 60 chart are similar to the age 65 chart, reflecting the same underlying investment portfolios used in the simulations.

To clarify the Mullaney’s choice, the table below lists a subset of the years represented in the charts for the “age to retire” decision and the “how to invest” decision. Suppose JG and Beth focus on their optimal spending prospects at age 75. If the Mullaney’s retire at 60 and want to choose the safer portfolio, their spending range at age 75 varies between $185k and $275k. Retiring at age 65 with the same investment portfolio uplifts the range to between $217k and $319k. The riskier investment choice widens the optimal spending range considerably. Retiring at age 60 and electing the riskier portfolio could lead to a lower outcome, but note the 50th percentile results. At this point, 50% of the simulated trajectories had total lifetime discretionary spending above the threshold as below. The 50th percentile results if investing in a risky portfolio is $281k but with a far more significant upside than a safer investment. A safer investment has a 50th percentile value of $244k, and the 95th percentile is only $275k. This latter choice may be most suitable for JG and Beth. Their taste for risk matters, and it may be their preferred choice if they are more risk-averse. A little less risk-averse may lead them to invest in the riskier asset choice.

One last way for JG and Beth to examine the investment choice question is to isolate a near-worst-case scenario. What is the downside risk to their optimal amount of discretionary spending? How low might discretionary spending go when subject to investment risk? The chart below shows the 5th percentile of optimal discretionary spending outcomes. For example, 95% of all optimal discretionary spending trajectories lie above these lines. In other words, it helps the Mullaneys assess their optimal spending floor.

It is evident that about $128k is the starting spending floor for both alternatives, and then they vary by age when one strategy is higher. The low point for the risky strategy for this simulation is at age 63, with an optimal spending amount of $104k. A lower-risk strategy never reaches that point.

How Advisors Can Help

The results for the Mullaneys show how investment risk and their t’ taste for risk are important to their retirement decisions. Advisors are skilled at helping their financial planning clients assess their risk tolerance.

That assessment can be put into an economics-based context to help with decision-making. Given Mullaney’s results, they should choose the safer investment option if they have very little tolerance for investment risk. However, if they can tolerate some risk, they should select the riskier investment option. The risk analysis section of their offers the details. Send me a note if you would like a PDF.

In the simulation, 500 trajectories are built. Trajectories are ranked based on their cumulative lifetime living standard.