Kate and Jamie are old enough to work full-time and young enough to be instructive about Gen Z’s interest in work-life balance.

Retired? Stay with us. The story is broadly relatable.

Our biggest asset is our ability to derive an income. Economists call it “human capital.” Think of human capital as income that makes our lives tick.

50-year-olds and 65-year-olds have human capital…..if they are interested and able to work.

This prior post has been updated and includes class notes for the Start Here series.

How Much Are You Worth?

Have you ever wondered what you will earn for the balance of your working lifetime? Toiling away, making ends meet, and living a daily life are normal for us. If you are under age 40, you might be amazed at your worth.

In the classroom, l often use the phrase “a cocktail napkin approach” to convey to students an estimate, an approximation of the financial metric du jour. For instance, “Let’s take a cocktail napkin approach to estimating your English prof’s human capital.” Haha. If the prof overheard the result, they would grab their edition of Leaves of Grass and run to the nearest bar!

So, what do we mean by human capital?

Human capital is the sum of your future, expected earnings from work. Sure, some arm-waving is involved, as in any estimation procedure that forecasts over many years. It does not mean the concept is uninformative. Forecasting future earnings is risky as the years of work lengthen; the human capital valuation for a 22-year-old is more complex than for a working 55-year-old. However, the principles of valuation are the same.

Kate and Jamie

Imagine what the human capital value must be of two friends, Kate and Jamie, who grew up together in north Texas.

Kate and Jamie started down different financial paths. Kate just graduated from a D1 university. Jamie started work two years ago at Texas Instruments in payroll and budgeting after receiving her associate’s degree from Collin County Community College. Kate and Jamie met during high school at Plano West in Plano, Texas, and live near each other in one-bedroom apartments on the Katy Trail near downtown Dallas. Sharing green eyeliner and hanging out with a refreshing drink is their manner. While both work in Texas, neither married nor does either have children. Great friends, different incomes, different living standards, all else equal.

Estimating Human Capital

Let’s start with Kate, the college grad.

The National Association of Colleges and Employers has data to get us started. The table below offers 2024 projected salaries for Bachelor’s degree holders by broad category and academic major. Engineering and computer science are the leading fields. Kate’s economics major falls within the Social Science category, so we assume a first-year salary of $69,802.

Jamie is a payroll staffer, and individuals in this occupation earn less money.

Want to know what people make, on average? The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates is a great resource for the average wage across occupations.

Want to know the average salary of a more obscure profession like a coach in an elementary or secondary school? Then look here.

In our example, the annual mean wage for Jamie’s payroll clerk career choice (search the site by occupational classification 43-305) is $54,690. Compared with Kate, there is a $15,000 annual difference.

Forecasting Earnings is Risky Business

Now for a bit of informed economics arm-waving. Human capital (HC) today is based on a lifetime of work, so we need to take the single, near-term annual earnings estimate and grow that salary amount by some rate for each year into the working future. But at what rate? I hate using a rule of thumb, so here is some empirical data. Since 1980, the average rate of increase in real wages has been near 0, about 0.332%.1 As a general rule, average salaries have grown commensurate with inflation. That is, salaries have remained flat in real terms. Like each of us, Kate and Jamie aspire to more frequent and significant income raises than their occupational peers, but for our purposes, we rely on the average of the observables. Therefore, the HC values for Kate and Jamie consider their work lives until retirement at age 69 and, in real terms, sum up the salary levels.

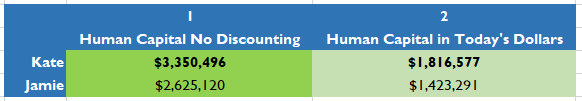

Column 1 of the table below rolls up potential future income. Kate’s talents, abilities, and job opportunities give her $3.35 million of HC. Jamie has a position less valued in the market than Kate’s but still retains about $2.62 million of HC. Column 2 provides a more appropriate measure of today’s real human capital dollar because it discounts at 3% the projected future earnings back to the present, reflecting that having a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future. Still, $1.8 million in today’s dollars for Kate conveys a valuable asset (she is a millionaire!), about $350,000 more than Jamie, who is also a millionaire.

Separating from Kate and Jamie, consider a more general approach to estimating human capital.

To estimate your human capital, what do you need to know? The number of years one can work in a career is important. Will there be job switching? Is it a field where incomes are expected to grow? When will you retire, if at all?

Some jobs have finite time paths. Think Tua Tagovailoa or a residential roofing laborer in San Antonio. Coders can work for many years. Boxers, not so much.

There is another extreme. Retirement isn’t for everybody. Spoiler alert to planners that push “saving for retirement.”

More years of work life create a higher living standard during our lifetime. However, many other factors, some of which are not within our control, impact the value of human capital. Raw talent, marketable skills, job choice, health, the state of the economy, and the risk of injury are the most obvious ones. Education, however, is normally a choice.

Education Matters

Ever heard these phrases: “Go to college,” “stay in school,” “do well in school?” The Kate/Jamie difference illustrates the value of more education. Below are more general findings from the College Board consistent with this one difference between Kate and Jamie.2 The figure below documents median earnings by educational attainment. The vertical axis is education level, and the horizontal bars reflect total median earnings, after-tax earnings, and estimated taxes. Higher levels of take home pay are associated with higher levels of educational completion. This is just a single year’s worth of earnings. Compound those across a working lifetime, and substantial living standard differences will exist.

Economic Risks to Human Capital

If HC is a household’s primary economic asset, risks beyond poor estimation are consequential to periodically updating a financial plan. What can cause HC to vary?

Some variability may be due to choice:

Job change - To a new, higher-paying job or a job change to one with lower pay.

Retirement preferences change - In a few years, the dream of an early retirement is replaced by the desire to work longer. Conversely, the person who thought they would never retire decides to buy an Airstream Bambi, go off the grid, and drive to Montana to think about obscure math problems in Glacier National Park.

Some variability may be out of a household’s control:

An inheritance - Receiving an inheritance changes the need and desire to work. Human capital is replaced by financial securities or more real estate. In this case, there will be assets to support the household living standard.

A pure risk - Bad outcome risks that are disruptive but often insurable. Unemployment is an obvious one. Earnings drop to $0. Premature death is another where all future earnings go to $0, which can be financially traumatic for a dependent household. Disabilities are a pain. The injured earner is still around to consume. A crane operator who tears his rotator cuff playing weekend softball will lose earned income. The tree surgeon who falls fifty feet and breaks his leg will have a job-related disability likely covered by the workers’ compensation system. However, when benefits fall short of the pre-disability income, there will still be a financial loss.

The Millionaires

When Kate and Jamie learn they are prospective millionaires with all the comfort that entails, it is not a free lunch. Like each of us, Jamie confronts the same risks to human capital as Kate. The key difference is that Kate has a higher prospective income floor beneath her. Due to different incomes, Kate and Jamie have different living standards. These friends may continue to hang out, but Kate may always buy the smoothies.

A geometric mean was calculated from LEU0252881600A data downloaded from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

From the College Board’s Education Pays site.

I think looking at human capital over a lifetime is the best way to really compare differences in income. The differences in levels or types of education become very clear when looking at the overall human capital. It's a great indication that can drastically show the differences in order to make financial decisions for now and for the future.

I like how this post teaches people to consider their worth over a lifetime of working and their personal needs. I was surprised by how much employer contributions could affect a 401 k outcome in the long run. This post definitely gave me a lot to consider when looking at my future benefits when applying for jobs.